Introduction

The preponderance of special operations forces (SOF) missions requires non-SOF support.01 There is only one Army Space officer (Functional Area 40) at every theater special operations command (TSOC) and Special Forces Group (SFG).02 These officers have an outsized impact on what commanders and units of action can accomplish operationally, or when preparing units of action to deploy forward (organizing, training, and equipping). At a TSOC, developing and directing lines of effort against an adversary’s communications architecture demands as much analytical rigor as ensuring units of action are properly equipped and trained to successfully contribute to a TSOC’s campaign support plan. While the Army’s talent management system has made positive strides in recent years, screening Army Space officers for service at SFGs or TSOCs warrants additional scrutiny. The suggestions below are scoped to Army Space officers due to the backgrounds of the authors, but this model could be applied to other low-density jobs in SOF, such as cyberspace or electronic warfare.

The screening and interview process needs to move beyond a 20-minute engagement in which the gaining command is unsure of the criteria, key skills, and attributes they should be assessing for. Selecting the appropriate Army space officer to serve at the TSOC or SFG will deliver outsized relative advantages to the joint force across the competition continuum and at all levels of war. This proposed assessment may sound costly, but it is much less expensive than having the wrong person lead and synchronize an entire domain of warfare for three years within that SFG or TSOC. United States Army Space and Missile Defense Command (USASMDC) needs to work in cooperation with the United States Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) to develop a two-phase assessment for Functional Area 40s (FA40s) electing to serve at TSOCs and SFGs. This proposed assessment is based on the assessments already under the purview of the United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (USAJFKSWCS). USAJFKSWCS is a two-star command that conducts three of the five assessments and selections for USASOC.03 This assessment, based on historical precedent, will highlight weighted attributes regarding operational planning acumen, previous experience with special operations forces (SOF), relevant space experience, cognitive agility, and courses that lend themselves to facilitating interoperability with SOF. While USASMDC and USASOC will develop the assessment, it will still be executed by the gaining unit’s FA40 and select staff members. This will enable leadership at the TSOC or SFG to better assess FA40s. It should be emphasized that not having the skills or attributes below would not be considered derogatory towards the applicant; rather, graduates of the courses below may find themselves more successful within SOF, given the unique mission set. The suggested weighted criteria will be examined in two macro phases: virtual and in-person.

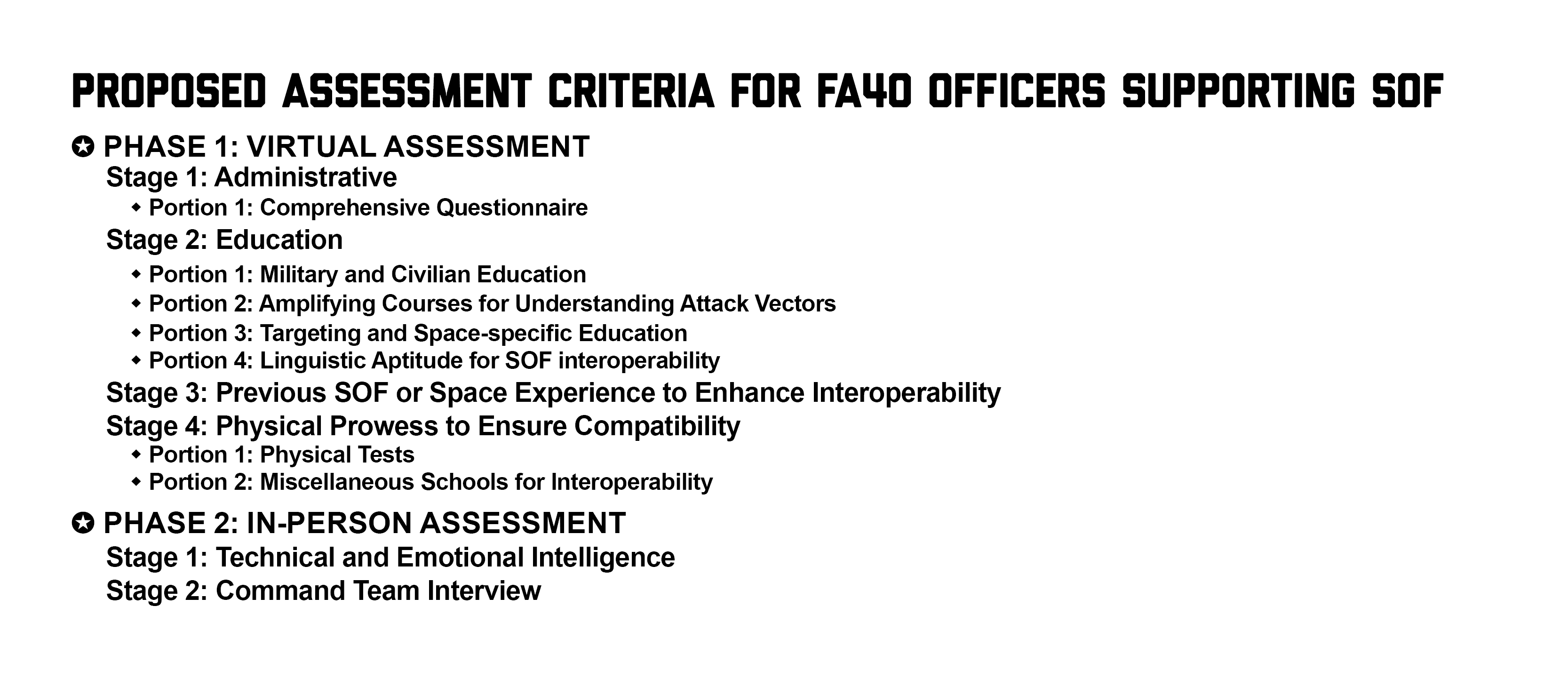

Figure 1: This graphic represents an outline of the proposed FA40 assessment for those Army Space officers electing to serve at TSOCs or SFGs.

Phase 1: Virtual Assessment

Comprehensive Questionnaire: Phase one of the virtual assessment is broken down into four stages, each warranting additional analysis: administrative, education, experience, and physical. The first sub-step of the virtual phase should be an administrative packet that is sent to the incumbent FA40, deputy commander, or chief of staff of that TSOC or SFG. These individuals will be responsible for assessing packets and coordinating with the Army’s Human Resources Command. That packet will include a questionnaire that probes the intricacies of that officer’s personal and professional life, their approach to learning, short-answer questions to assess their capacity for effective written communication, financial stability, outcomes of past leadership roles, moments of failure, and how that officer maintains a work-life balance. Other portions of the administrative packet should include score cards from physical events, a performance assessment from the officer’s current commander (colonel equivalent), the officer’s last five evaluations, and the officer’s Soldier Talent Profile (STP). All civilian and military education suggestions from the Army space officer professional development guide, as delineated in the Department of the Army Pamphlet 600-3, have been accounted for in subsequent sections; however, additional courses should be favorably considered when assessing the interoperability of space officers with SOF formations.

Military and Civilian Education: Within this second stage of the virtual screening process, how does the applicant ingest and synthesize information? Have they attended any meta-cognition courses such as Red Team Member, Red Team Leader, the School of Advanced Warfighting, the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, or the Advanced Military Studies Program? Graduates of these schools spend a year learning how to think and how to campaign at an operational level by synchronizing tactical actions across time, space, and purpose. They are equally adept at campaigning against an adversary as they are at preparing units for deployment, and would be a value-added team member at a TSOC or SFG. Does the space officer have a relevant undergraduate degree, advanced degree, or certification(s) related to their career field? Has the officer completed the second phase of joint professional military education, thereby increasing their effectiveness in a joint environment? While not a requirement for success, space officers who elect to continue advancing their education through opportunities presented by the Army or on their own are demonstrating the intellectual tenacity necessary to thrive in the SOF community.

Amplifying Courses for Understanding Attack Vectors: The second portion of the education stage examines the other military or civilian schools the applicant has graduated from. Courses focused on military deception, network development, and cyberspace all provide supplemental knowledge for an FA40 to integrate amongst the staff. Gaining units should understand that war is still a human endeavor, and satellites are therefore a means to target the adversary end user in the terrestrial segment. Space warfare, especially in competition, is as much a cognitive battle as it is a kinetic one.04 Finally, space warfare can be thought of in part as a war of information, as a struggle between the effective collection and dissemination of bytes to the appropriate user. This becomes pivotal when examining vulnerabilities in the terrestrial segment. Not only does it enable the FA40 to propose additional access vectors to create dilemmas, but it also allows them to pose more effective questions to staff members with a background in cyberspace operations.

Targeting and Space-specific Education: The third portion of the education stage explores the officer’s understanding of joint targeting, foreign electronic warfare assets, and space-based platforms. Can they apply that knowledge to web-based services that can facilitate the targeting cycle? Can they integrate technical operations to augment SOF operations, activities, and investments? FA40s will be asked to contribute to the targeting cycle across the competition continuum, so being able to support the fires warfighting function should remain at the forefront of the gaining unit’s weighted criteria. The STP will only indicate their graduation from these courses. However, the commander’s assessment and evaluation reports may indicate whether the officer applied that knowledge during the pre-mission training cycle, during named exercises, while deployed, or concurrently with their time on staff.

Linguistic Aptitude for SOF Interoperability: The fourth portion of the education stage is linguistic capability. Can the space officer speak an additional language that would advance the mission set of that SFG or TSOC? Cultural fluency affects every warfighting function and will continue to decrease the efficacy of theater-strategic campaigning if not adequately accounted for. The space domain is not an exception to this. Coupled with technical knowledge, the ability to speak the target language(s) for that SFG or TSOC will enhance Army Space Officers’ support in deriving a space-centric approach to the operational variables and their impact on operations, activities, and investments throughout the competition continuum. In the near future, space officers will conduct tactical and operational-level engagements with host nation counterparts alongside their SOF partners during Joint Combined Exchange Training or, more broadly, under the auspices of building partner-nation capacity. Tactical U.S. Space Force elements will have a small role to play in developing a nation’s orbital warfare portfolio, and the preponderance of nations where SOF has access and placement are “emerging space powers” at best, predicated on the fact that they have the scientific and industrial base to build a satellite at all.05 These nations are more interested in delivering effects to space, or receiving effects from space, to support their warfighters. For that reason, the FA40 is the appropriate officer to facilitate those engagements in the host nation’s language. This will be an evolution of building partner nation capacity, and FA40s should rise to meet this challenge.

Previous SOF or Space Experience to Enhance Interoperability: The third stage of the virtual phase is screening for prior experience within SOF and in the space community. Officers within special operations are held to a high degree of professional acumen, and space officers assigned to special operations units should be held to the same standard. SOF officers are expected to brief all levels of war—from tactical schemes of maneuver to theater-strategic campaigns— and to address equities across the joint, interagency, intergovernmental, multinational, and commercial environment. Suppose SFGs or TSOCs can find Army Space Officers who were previously Army Special Operations (ARSOF) officers. In that case, those officers may be better postured to serve the USASOC enterprise as space professionals, having previously worked in the community. Conversely, tenacious FA40s who spent their captain time being involved in space control may prove just as valuable to advancing SOF OAIs. FA40s who oversaw space control planning teams, or managed the staffing of those products, and participated in relevant exercises or deployments, may prove more fruitful than an FA40 who has had a different career track. In the years to come, this recruitment pool will extend to the FA40s assigned to the multidomain effects battalions and the theater strike effects group. As a final consideration, space control planning teams are regionally aligned, similar to ARSOF units of action. This sustained regional alignment fosters familiarity with the pacing and acute threats outlined in the National Security Strategy while enabling the SOF community to leverage a different vantage point.

Physical Prowess to Ensure Compatibility: The fourth stage of the virtual phase is assessing how well the officer can perform a variety of physical tasks. Most of the current interview process is conducted digitally to maintain a semblance of fairness. This will have to continue until the top three candidates are chosen to attend the in-person assessment with their respective gaining units. An Army Fitness Test scorecard should be part of the applicant’s packet, along with the finished time for events such as a 12-mile road march with 35 pounds, a five-mile run, and a grade sheet for the upper body round robin test.06 A senior non-commissioned officer at the officer’s current unit will administer and grade these events. All events will be re-administered to the top three candidates upon their arrival for the in-person selection. The physical events should be weighed more heavily for FA40s electing to serve at the SFGs versus the TSOC.

Miscellaneous Schools for Interoperability: The second portion of the fourth stage captures a set of skills that is admittedly between the physical and the mental, but should be assessed, nonetheless. Acknowledging that paid parachutist positions are being reduced, SOF units remain airborne units that specialize in operating in denied or politically sensitive environments.07 Favorable criteria would then extend to the FA40 applicant being airborne qualified, a static line jump master, ranger-qualified, other advanced ARSOF courses, or a graduate of advanced iterations of the Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape school. FA40s applying to work within SOCOM, who are graduates of these schools, are postured to maximize interoperability. Having the requisite capability to support the unit of action would allow the team to focus on their core tasks instead of learning the intricacies of a new piece of equipment. With all the weighted preferences to consider, the incumbent FA40, deputy commander, or chief of staff, will have to evaluate the criteria as they see fit against their mission set and invite the top three candidates to phase two, the in-person assessment.

Phase 2: In-Person Assessment

The second phase in the screening process involves the applicant traveling to the gaining unit. The screening lasts no longer than three days to afford the command the most holistic assessment of the candidate without placing undue stress on the staff. No more than three candidates should be assessed to the final stage to avoid overburdening the operational psychologist (OpPsych). The candidate will be administered a series of personality tests and cognitive assessments. The cognitive assessments will include essay questions, short answer questions, ethical queries, and space-centric technical questions. If the gaining unit is short on money, these tests could be administered virtually, with the original fitness metrics being placed in the candidate’s final file for the command team. The number of potential candidates could also be reduced to two to alleviate financial burdens.

Technical and Emotional Intelligence: During this three-day assessment, the candidate will interview with the OpPsych assigned to that SFG or with the TSOC to determine whether that officer is an appropriate fit for that organization. The OpPsych will compile a dossier that includes all the officer’s evaluation reports, the initial administrative packet, a third-party social media scrape, cognitive test outcomes, writing samples, and results from the candidate’s personality tests.08 Questions during the OpPsych’s interview will explore the officer’s tenacity, intellectual humility, moral parameters, ethical boundaries, and self-awareness. The OpPsych will provide their assessment to the command team regarding whether that officer is a good fit for the unit and its culture, whether the officer can operate as part of a team, and how they respond to external stressors. In addition to the OpPsych’s interview, the candidate will conduct an oral technical interview, chaired by the incumbent FA40, to supplement the written technical questions. This allows the unit to gauge the officer’s ability to brief, cognitive dexterity, mastery of doctrine, and to observe any non-verbal tics that would otherwise not be readily apparent. The candidate will also be re-administered the same series of physical tests if the assessment is conducted in person.

Command Team Interview: The results of the technical interview are compiled with OpPsych’s assessment and combined with the other dossier components for the command team to conduct its final interview with the candidate. At the conclusion of all three interviews, the commander will make a hiring decision and inform the chosen candidate.

Conclusion

Special Forces groups and theater special operations commands should establish weighted preferences and a selection process for Army Space officers. Favorable characteristics include cognitive agility, previous SOF experience, relevant space experience, cultural acumen, physical fitness, and technical capability. The correct Army Space officer has the capacity to facilitate multiple dilemmas on the periphery, or in the strategic deep of adversaries delineated in the National Security Strategy. A three-day assessment for three officers may sound costly, but it is much less expensive than having the wrong person lead an entire domain of warfare for three years within that SFG or TSOC. The weight of each attribute and quality discussed in this paper will vary by command, depending on the operational variables for that area of responsibility. While this proposal is admittedly scoped to Army Space Officers, it could serve as a model for other low-density skills across the USASOC enterprise to ensure SOF leaders have enablers who are as professionally impatient and resourceful as their operators.

Authors’ Note:

Brigadier General Donald Brooks, U.S. Army, is the deputy commander for operations at the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command. He was the first FA40 to serve at a TSOC, and established USSOCOM’s Joint Integrated Space Team. Brigadier General Brooks commanded the Army’s 1st Space Brigade and advanced Army Space equities in support of Lt. Gen. Jonathan Braga’s Space-SOF-Cyber Triad initiative. He holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the U.S. Military Academy and a master’s degree in earth remote sensing/ hyperspectral imagery from the Florida Institute of Technology. He completed the U.S. Army War College as a Fellow at the Georgia Institute of Technology in 2020. Brooks previously served as commandant of the Space and Missile Defense Center of Excellence.

Major Brian Hamel, U.S. Army, serves as a Space Operations Officer for a unit within USASOC that focuses on transregional irregular warfare. He holds multiple advanced degrees and has deployed to multiple theaters to support special operations. His previous articles focus on special operations forces’ contributions to space warfare, operationalizing celestial lines of communication for materiel delivery, and planning considerations for transregional irregular warfare.

References

01 Headquarters, U.S. Special Operations Command, “SOF Truths.” August 10, 2025. https://www.socom.mil/about/sof-truths.

02 Headquarters, US Army Space and Missile Defense Command Center of Excellence. “

FA40 Roster.” (October 2024): 2-14.

03 Headquarters, United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, “Qualification Courses Overview.” August 10, 2025.

https://www.swcs.mil/Schools/Qualification-Courses/.

04 Hamel, Brian. “Reframing the Special Operations Forces-Cyber-Space Triad: Special Operations’ Contributions to Space Warfare.” December 2024. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/March-2024/Cyber-Space-Triad/.

05 Klein, John J.

Space Warfare. London: Routledge, 2005.

06 Smith, Stew. “Prepare for Special Ops Testing with the UBRR Pyramid.” August 10, 2025.

https://www.military.com/military-fitness/prepare-special-ops-testing-ubrr-pyramid

07 Headquarters, Department of the Army. Army Doctrine Reference Publications 3-05,

Special Operations. Washington, DC: Army Publishing Directorate, June 2025.

https://irp.fas.org/doddir/army/fm3_14.pdf.

08 Headquarters, U.S. Army, “Commander 360 Program.” December 5, 2014.

https://www.army.mil/standto/archive/2014/12/05/.