Air Force Doctrine Publication 1 discusses mission command as a product of trust.

01 It is a philosophy of leadership that empowers commanders and operators in uncertain, complex, and rapidly changing environments through trust, shared awareness, and understanding of the commander’s intent. Think back to Nimitz, the technological challenges of his era

required trust, though it was his way of command regardless.

02 Modernity, conversely, does not inherently demand it; in fact, it often eschews trust, with compartmentalized information viewed as devoid of the necessary context for proper understanding. The ever-present challenge in modern military affairs persists: higher headquarters making snap judgments without grasping the “atmospherics” of the situation.

03 What then should commanders do with their pixel of information?

“It is for situational awareness,” they protest.

Yet, many wars have been fought and won without the commander in the echelon above knowing

precisely what was unfolding below.

Modern operations, with all of their interconnectedness, must serve as both a testing ground and a crucible, forging trust between echelons. This trust, of course, is a two-way street, bidirectional, and every party must establish a shared understanding of the default measure of confidence. Subordinate commanders must

trust that their superiors have conducted the necessary analysis and issued clear orders with the correct intent. In turn, the superior must

trust that the subordinate tactical-level commander is acting in good faith, operating within the confines and the spirit of the given order. Interloping in such a command structure cannot be tolerated.

There is an undeniable human element—call it part curiosity, part hubris. The perceived “need” for superior commanders to intervene in their subordinates’ tactical operations and dictate employment must be founded on something substantive. Yet, it is significantly challenging to attribute this impulse to anything beyond, “Well,

I wouldn’t do it that way. He must not know. I will straighten this out.” Instead of rectifying an issue, such intervention by superior commanders, more often than not, muddies the waters. It creates confusion and extends the kill chain.

04

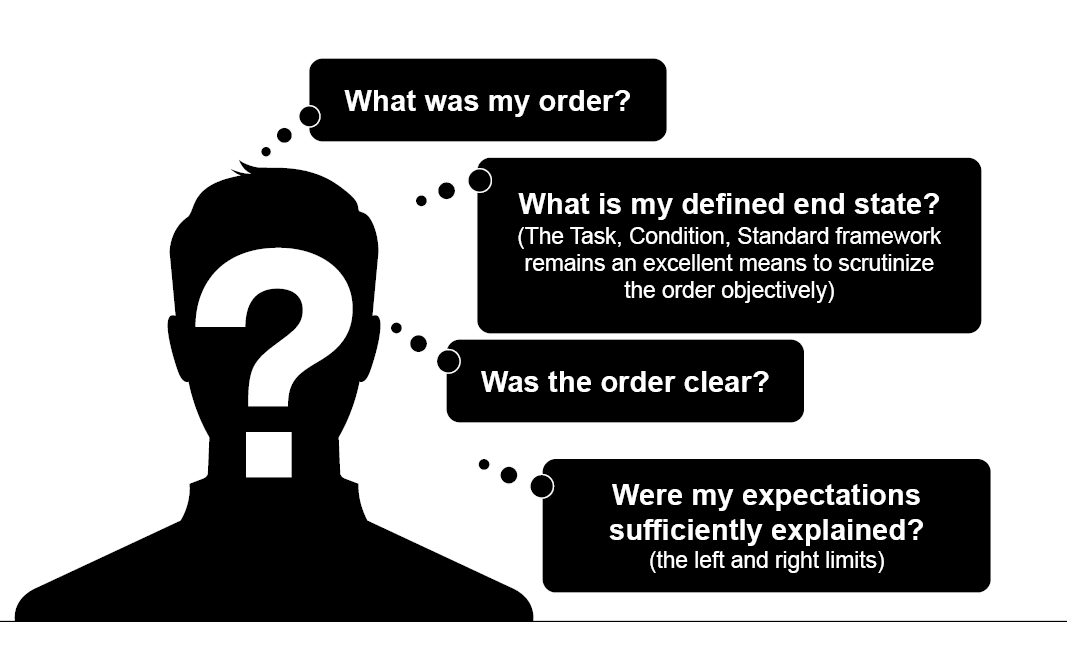

Consider a hypothetical situation: If a subordinate commander is not performing to the liking of a superior, and that superior feels the “need” to involve themselves, who is truly at fault? Before superior commanders interject, they must first undertake an introspective assessment:

Commander introspective assessment questions. What was my order? What is my defined end state (The Task, Condition, Standard framework remains an excellent means to scrutinize the order objectively)? Was the order clear? Were my expectations—the left and right limits—sufficiently explained? (Illustration by Special Warfare Staff)

Commander introspective assessment questions. What was my order? What is my defined end state (The Task, Condition, Standard framework remains an excellent means to scrutinize the order objectively)? Was the order clear? Were my expectations—the left and right limits—sufficiently explained? (Illustration by Special Warfare Staff)

If all these questions can be answered affirmatively by

both parties, and corrective action is still demonstrably necessary, then, and only then, is superior echelon involvement warranted.

Let us introduce another wrinkle to this scenario: Assume all the above conditions are met—the order is clear, understood by both superior and subordinate—and the superior commander then receives (or already possesses) additional intelligence of vital importance. What, then, is the superior’s course of action? They must inform the subordinate and, depending on the nature and criticality of the intelligence, either recommend or, if necessary, order an immediate adjustment to tactical operations.

Forging the Future Force: Mandates for Modern Military Leadership

How then does the U.S. military prepare itself, not merely to adapt, but to dominate the battlefields of the next century and maintain its position as the predominant military power? The path forward requires a conscious evolution in command philosophy, centered on three core imperatives: unwavering trust, empowerment of subordinates, and the adaptation of the modes of command to the realities of future warfare.

The Bedrock of Trust

The cultivation of trust within a command climate cannot be a passive acknowledgment; it must be an active and relentless pursuit. Commanders,

at every echelon, must labor to establish trust not as a reward for flawless performance, but as the default. The illusion of perfect oversight, offered by modern technological connectivity, must be recognized for what it is: a corrosive to the imperative of trust. Digital omnipresence does not negate the need for commanders to trust their subordinates, and for subordinates to trust their superiors. Indeed, the tendency for higher headquarters to render snap judgments that are by their nature devoid of tactical realities must be actively and systemically countered.

Confronting Hubris

The human element—that potent cocktail of curiosity and

hubris—which fuels the perceived “need” for superior commanders to delve into the tactical minutiae of their subordinates’ operations, must be confronted and mitigated. Before such intervention, a rigorous and honest introspection is demanded. Was the order unequivocally clear? Was the end state defined with precision? Were the operational boundaries and acceptable risks sufficiently articulated? Only when these questions are met with an affirmative, and a genuine shortfall in execution persists, should a superior commander’s involvement be warranted to avoid catastrophe.

The Foundation of Disciplined Initiative

The articulation of clear, concise orders, anchored by well-defined end states and explicitly communicated risk parameters, is paramount to the concept of mission command.

05 This clarity is the bedrock upon which subordinate commanders can exercise disciplined initiative, which is the beating heart of agile and adaptive forces. Should intervention become necessary, it must proceed from a shared, unambiguous understanding that all parties comprehended the initial directives, or be precipitated by the emergence of new, critical intelligence that fundamentally alters the operational calculus.

Forging Trust Under Fire

Contingency and expeditionary operations must be viewed through a dual lens: not merely as missions to be executed, but as crucibles for tempering trust between commanders, which demands an unwavering, bidirectional commitment. Subordinate commanders must operate with the conviction that their superiors have conducted the requisite analysis and issued sound strategic intent. Conversely, superior commanders must vest their trust in the good faith and professional competence of their tactical leaders to act within the confines and spirit of the order. Interloping, in such a system, is not merely unhelpful; it is an intolerable friction upon the architecture of command.

Delegated Authority

While the pursuit of information dominance remains a cornerstone of modern military strategy, its practical utility is severely limited if the appropriate authority to act upon that information is not granted to the

tactical echelons. The conflation of enhanced information access with an assumed necessity for centralized decision-making is a dangerous fallacy.

06 It is a path that invariably curtails agility, blunts initiative, and diminishes the capacity of tactical commanders to seize fleeting opportunities.

The Imperative to Decentralize Now

The “luxury of connectedness,” a defining feature of the Global War on Terror, is an indulgence the future battlefield does not afford.

07 Acknowledging this stark reality demands an immediate and active refocusing on communicating strategic intent and apportioning risk in a manner that

enables subordinate commanders to operate effectively. To

restrict a commander in environments that are characterized by degraded or denied communications is a fool’s errand and destined for calamity. To fail in adapting command philosophies

now, in an era of limited conflicts, is to actively prepare for failure when the specter of total war rears its head.

The deliberate embrace of these principles is not merely advisable; it is essential. Doing this today is how superior officers will cultivate a force that is not only more agile and adaptable but, ultimately, more lethal. This makes a force capable of thriving amidst the complexities and pace of modern warfare with all its uncertainties. The crux of this transformation resides in the oft-unglamorous labor of deliberately cultivating trust and unequivocally empowering the tactical leaders who stand closest to the combat.

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinions expressed in this writing are those of the Author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any specific organization, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The contents of this manuscript have been vetted and cleared through the Author’s OPSEC office.

References

01 Department of the Air Force,

Force Development, Air Force Doctrine Publication 1-1 (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Curtis E. LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education, 2021), 1.

02 For an exceptional look at Admiral Nimitz and his Command of the Pacific, see: Trent Hone,

Mastering the Art of Command: Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Victory in the Pacific, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2022).

03 For more information regarding the fallacy of "situational awareness" as a driver for centralization, see Milan Vego,

On Command: The Art of Command in Modern Warfare (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2021), 215.

04 Carl von Clausewitz,

On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 119. See Clausewitz’s discussion on Friction in war for a discussion on how simple things are difficult and that countless minor, unforeseen problems inevitably complicate execution.

05 Department of the Army,

Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces, Army Doctrine Publication 6-0 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2019), 1-3, 1-4, 1-14.

06 David Barno and Nora Bensahel,

Adaptation Under Fire: How Militaries Change in Wartime (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 267.

07 U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command,

The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1 (Fort Eustis, VA: TRADOC, 2018), 16-17; U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff,

Joint Operating Environment 2035: The Joint Force in a Contested and Disordered World (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, 2016).